Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

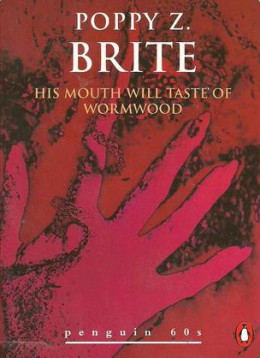

Today we’re looking at Poppy Z. Brite/Billy Martin’s “His Mouth Will Taste of Wormwood,” first published in the Swamp Foetus short story collection in 1993. You can also find it in a number of later anthologies, including Cthulhu 2000—but probably should not go looking if under 18. Spoilers ahead.

“To the treasures and the pleasures of the grave,” said my friend Louis, and raised his goblet of absinthe to me in drunken benediction. “To the funeral lilies,” I replied, “and to the calm pale bones. I drank deeply from my own glass. The absinthe cauterized my throat with its flavor, part pepper, part licorice, part rot.”

Summary

Narrator Howard and his BFF Louis are dark dreamers. They met as college sophomores, a time of life when many find themselves precociously world-weary, but Howard and Louis are really bored. For them books are dull, art hackneyed, music insipid. Or, as Howard puts it, “for all the impression the world made on us, our eyes might have been dead black holes in our heads.” Ouch.

Obvious soulmates, they team up to find salvation from soul-crushing ennui. First they try the “sorcery” of weird dissonances and ultra-indie bands. Nope. On to carnality. They exhaust the erotic possibilities of women, other men and the occasional stray dog before turning to each other for the extremes of pain and ecstasy no one else can give them.

When sex palls, they retreat to Louis’s ancestral home near Baton Rouge. Since his parents died by suicide and/or murder, the plantation house has stood deserted on the edge of a vast swamp. At night the pair loll in an alcoholic haze on the porch, discussing what new thrills they should seek. Louis suggests grave-robbing. Howard’s dubious, but Louis waxes poetic on the joys of setting up their own private homage to death, and eventually Howard succumbs to his fervor.

Their first trophy is the rotting head of Louis’s mother, which they enshrine in the basement “museum” they’ve prepared. Soon it’s joined by other grisly remains and grave-booty, including fifty bottles of absinthe liberated from a New Orleans tomb. They learn to savor the pepper-licorice-rot taste of the wormwood spirit.

Rumor and the mumblings of an old blind man lead them to the grave of a voodoo priest who once ruled the bayou. They unearth a skeleton still clothed in parchment skin and adorned with an eerily beautiful fetish: a sliver of polished bone—or a fang-like human tooth—bound in copper, set with a ruby, and etched with an elaborate vévé—a voodoo [sic] symbol used to evoke “terrible gods.” Louis claims the fetish as their rightful plunder.

The pair plan a debauch to celebrate their latest acquisition. Louis wears the fetish as they visit a graffiti-scrawled club; in the restroom, Howard overhears two boys talking about a girl found dead in a warehouse, her skin gray and withered, as if something had sucked out the meat beneath. At the bar a ferally beautiful boy admires Louis’s “amulet.” It’s voodoo, the boy says, and it doesn’t represent power as Louis claims. No, it’s a thing that can trap a soul, dooming it to eternal life.

Why should eternal life be a doom rather than a blessing, Louis wonders.

Why don’t they meet later for a drink, the boy suggests. He’ll explain further, and Louis can tell him all he knows about voodoo. That last makes the boy laugh, and Howard notices that he’s missing an upper canine tooth.

Howard doesn’t remember much about the rest of the evening, except that the boy goes home with them, to drink glass after glass of absinthe and join them in their bed. There he whispers what might be incantations. His mouth tastes of wormwood. He turns his attentions from Howard to Louis. Howard would like to watch, but he passes out.

When he wakes, the boy’s gone and Louis is a desiccated corpse. At the foot of the bed is a vaguely humaniform veil, insubstantial as spiderweb.

Howard places Louis’s brittle remains in his mother’s museum niche. Then he waits for the boy to return, haunts the club where they met. Couldn’t death be the sweetest thrill after all? Howard will find out when he reopens that grave in the bayou boneyard. He’ll see its sorcerous occupant young with Louis’s drained youth and wearing the reclaimed fetish.

The boy will invite Howard into his rich wormy bed, and his first kiss will taste of wormwood. The second will taste only of Howard’s siphoned-away life.

The pleasures of the grave? They are his hands, his lips, his tongue.

What’s Cyclopean: This story’s language is gorgeous, from the estate’s “luminous scent of magnolias” to the sorcerer’s “scrimshaw mask of tranquility.” But there’s one truly strange description: the scent of the grave is “a dark odor like potatoes long spoiled.” This has happened in my cabinet a couple of times, but somehow it never made me think romantically of death so much as desperately of the distance to the trash can.

The Degenerate Dutch: Though the vévé is robbed from a “Negro graveyard,” the homme fatal sorcerer who comes seeking it is beautifully pale. “A white voodoo priest who had ruled the bayou.” What these people need is a goth-boy?

Mythos Making: The plot of “Wormwood” is lifted almost whole cloth from Lovecraft’s “The Hound,” minus the Necronomicon and plus… things that Lovecraft never discussed explicitly, but that Brite covers at length.

Libronomicon: Louis and Howard find books dull. The more literate aesthetes of “The Hound” could have told them a thing or two about what taboos can be broken in the stacks at Miskatonic.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The beautiful sorcereor has a “cool elegance like a veneer of sanity hiding madness.”

Anne’s Commentary

I guess I had a little in common with Louis and Howard when I was a sophomore, because out of all the cheerful art prints in the college bookstore (Picasso’s Hands Holding Flowers! Monet’s waterlilies! Dangling kittens advising us to hang in there!), I chose Degas’ “Glass of Absinthe.” Dressed in dull browns and dirty yellows as dismal as her cafe surroundings, a woman sits beside a surly-looking man and gazes into the cloudy green depths of her wormwood cordial. Is she, too, looking for salvation from the sordid mundane? Is she hoping her (no doubt cheap) brand of absinthe will be enough adulterated by methyl alcohol and copper salts to kill her?

Death’s the ultimate escape, man. Also the ultimate sensation, if we’re to believe Lovecraft and Brite’s ghoulish aethetes.

Gotta say, I’m enchanted with Brites’s updating of “The Hound.” His imagery and descriptions are as simultaneously lucid and hallucinatory as absinthe’s legendary effects on its drinkers. They’re also as poisonous, though exquisitely so. His Howard, like Howard Lovecraft himself, is a poet intoxicated by the dark. He’s far less inhibited in his details of decadence, however. “Hound’s” narrator and his friend St. John go in for, ahem, “unnatural personal experiences and adventures” after literature and art cease to titillate. “Wormwood’s” Howard is frank about his and Louis’s sexual and necrophiliac excesses. We saw the same no-holds-barred approach to modernizing the Mythos in Fager’s “Furies from Boras,” but Fager wielded a warhammer spiked with profanity and gore, while Brite’s weapon of choice is more like a velvet-handled whip, deployed with a precision that draws blood—but never quite crudely. Which is hard to do when you’re writing about bestiality, unorthodox uses for rose-oil coated femurs, and casually wiping gobbets of your mother’s putrescent flesh from your fingers.

Brite’s allusions to his source material are thorough yet subtle. There’s the narrator’s name of course. There’s the mirrored situation of BFFs so jaded they must turn to grave-robbing for emotional stimulation. There’s the matching plot arc: the establishment of charnel museums in an old family manse, the acquisition of one bauble too many, the vengeance of its original owner. Details as small as an affinity for the scent of funeral lilies are echoed.

But greatest interest lies in the divergences, the homage’s personal twists. The setting is deftly switched from remote English moorland to the Southern Gothic meccas of Louisiana’s swamps and New Orleans’ dives. (I wonder if Brite is also alluding to Anne Rice by combining her two most famous vampires in the character of Louis, borrowing the “Interviewee’s” name and Lestat’s blondness, sartorial splendor and snarkiness. There’s also the curious emphasis on Louis’s light sensitivity, to counter which he wears sunglasses even at night.)

Another telling change is that Louis and Howard are, no apologies, lovers. Lovecraft dares only hint at that sort of relationship for his narrator and St. John.

The most important difference is that Brite can allow the terrible to be truly beautiful and alluring, disfigured only by the sacrifice of one canine tooth to make its fetish strong. Lovecraft’s avenging monster is a grinning skeleton borne by giant bats. Brite’s is a gorgeous young man who was even pretty good-looking as a dried-out corpse, I mean, if you go for that kind of thing. Lovecraft’s narrator will kill himself to escape the devouring maw of the Hound. Brite’s Howard seeks his “Hound,” longs for a life-draining embrace in the rich earth of his grave-bed. For both narrators, death is the only salvation, but Howard’s death entices with a certain sensual abandonment, while “Hound’s” narrator can look forward to only mortal agony or a bullet to the brain. Aw, Howard (Phillips Lovecraft, that is), your pessimist, you realist. You old-fashioned rationalist with the soaring cosmic vision, as opposed to this week’s thoroughly modern romantic.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

There is a frisson, somewhat akin to that one might feel surrounded by elaborately displayed mementi mori, in reading the stories of the dead. One is always aware that, by reading, one resurrects them in ghostly form, re-thinking the thoughts they had during a few living moments. Especially for the reader who is themselves an author, there is also the awareness of one’s own mortality, and the ephemeral thoughts not yet, or never, committed to paper and pixel.

A different sort of mortal awareness comes from reading a story, by a living author, that invokes a period of one’s own life now lost. In 1993, I was just starting college; I liked Anne Rice and Steven King, hadn’t yet figured out why Holly Near sang love songs “from the man’s point of view,” and wasn’t all that fond of people in general. Fresh out of the limitations of a home town with no public transportation, ennui still held some romantic allure. Eighteen-year-old Ruthanna thought Lestat was kind of dreamy, and if she’d encountered Brite at that formative age would have liked his work rather a lot.

And that’s who this story was written for. Brite was in his early 20s, deep in the closet in New Orleans, and had every reason to write a story in which gay sex was a sign of profoundest forbidden decadence, and the next thing to Beloved Death.

For forty-year-old Ruthanna, though, “Wormwood” is an excellent specimen of a thing I no longer enjoy. I am no longer excited by self-wasting romantic poets, no matter how well-written. Worse, the invocation of Louis’s mother flips my parent switch thoroughly—this is the (in this case extremely awkward) reflex that causes me to read stories, not from the perspective of the protagonist as intended, but from the perspective of their parents. At best, I want to tell Louis and Howard that if they can’t think of anything productive to do, there are dishes in the sink. At worst… I’m just gonna go curl up now and not think about that. Right. I’m gonna leave deep exploration of the sex-death dynamic to my own partner in crime.

Regardless of my personal aesthetics and squicks, Brite is in fact playing with Lovecraft in some interesting ways here. And with Rice—if the story’s skeleton is homage to “The Hound,” the skin pays tribute to The Vampire Chronicles. Certainly Lovecraft would have squirmed uncomfortably at seeing how Brite filled in what he firmly left to the imagination. Especially given “Howard” as the submissive member of our antisocial couple, matched against not-a-vampire Louis. I half-wonder if the story is intended as a commentary on why one might leave things to the imagination—it certainly works that way, even as it titillates and shocks with taboo-violation.

At that, though, the violation doesn’t really compare to the original. Transmuted from Lovecraft’s degenerate countryside to gothic New Orleans, you can still violate the laws of god and man, but the god in question is Catholic or maybe Voudun, rather than Mythosian. We get reference to an “incompetent black mass,” but no Necronomicon in sight to suggest more squamous misdeeds. Louis’s death is treated more as reward for sufficiently imaginative sin than as the demonic punishment of the original. Pretty Boy doesn’t object to his grave being robbed. If anything, he finds it amusing and somewhat endearing—amateurish evil, deserving of a condescending-if-fatal pat on the head.

“Hound” isn’t one of Lovecraft’s strongest, in part because it follows the typical script of a morality play, with the narrator surviving only long enough to repent of his theft, and by extension of the ennui that led to it. But Brite isn’t having any of that. His story is firmly on the side of decadence: Howard expects to receive his just reward, by his own definition if no one else’s.

From the urban horror of New Orleans, we turn next week to the horrors of the darkest woods in Algernon Blackwood’s “The Wendigo.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.